Vanceboro and Lambert Cemetery internment listings

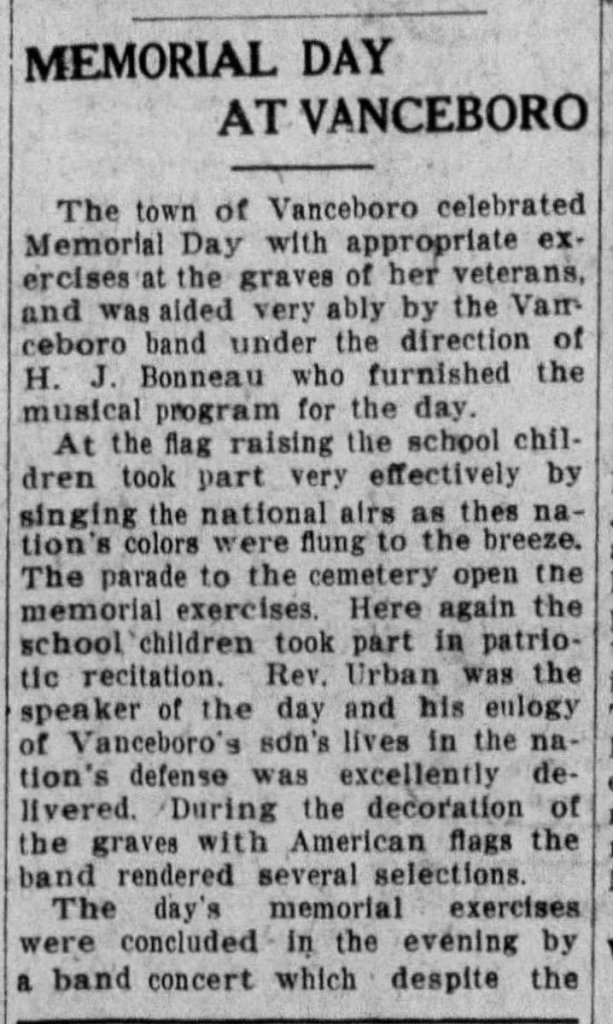

Memorial Day has always been a solemn occasion in Vanceboro. In such a small town everyone knew everyone. Many were related to those who went to war and so the whole town mourned those who did not come home. Mary McAleney lived along the road to the cemetery as a young girl in the early 1950’s, and remembers standing on her front porch with her brother, Mike, on Memorial Day. “We had risen early to help raise the flag in our yard. We waited and watched for the parade to pass by. There was a drummer and must have been other music. At age 5 I felt the sadness of the men and women who marched by and understood the solemnity of the occasion. After the parade passed by we would join and march to the cemeteries for the ceremony. The sound of TAPS brings me back to that day.” Jan Turiel lived across the street from the cemetery and remembers Taps and the 21 gun salute. “I still tear up when I hear them. I heard those sounds for everyone who didn’t make it home alive, as well. They are the saddest sounds I’ve ever heard to this day.”

The Civil War

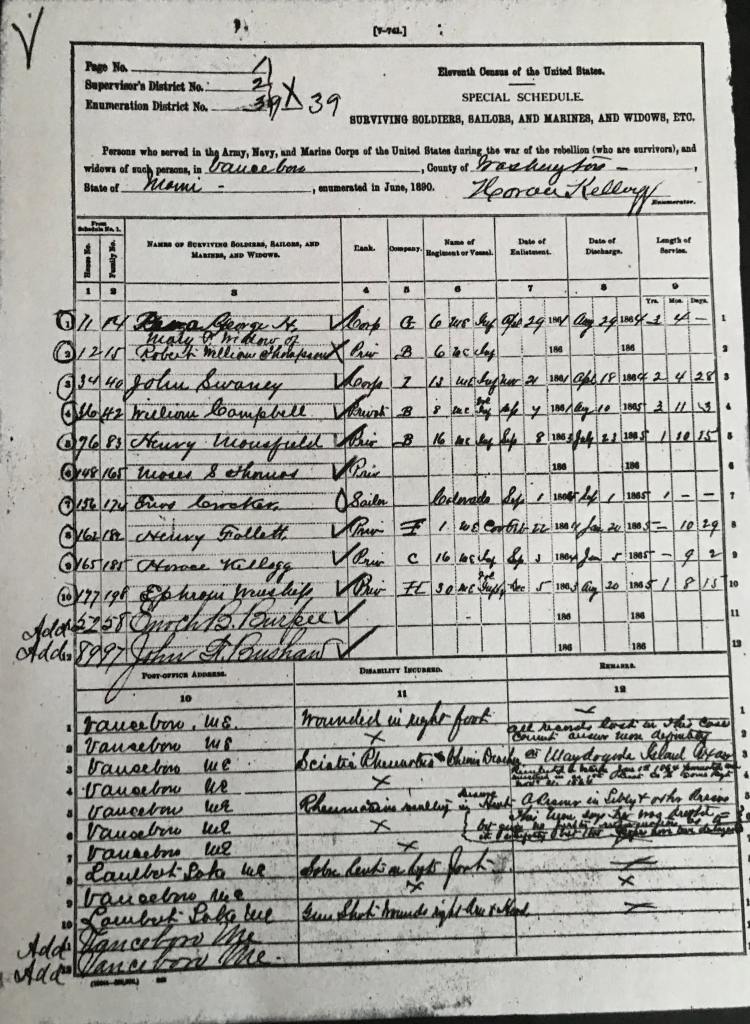

A number of Vanceboro’s earliest citizens were Civil War Veterans. John Swaney (1841-1912) served in the 13th Maine. He was 20 when he enlisted in November, 1961. He was discharged in April, 1864. Born in Lubec, he came to Vanceboro to work in the tannery. He was the first postmaster in town, and later he and his sons later ran an undertaking parlor — Swaney Brothers Undertaker. Henry Mansfield (1833-1905) arrived in Vanceboro from Mattawamkeag to work as a watchman for the railroad. He joined the British Navy as a young cabin boy, jumped ship after ten years or so, most likely in St. John, and made his way to Greenbush, Maine. He joined the northern cause as a substitute for a lawyer’s son in Eddington. He was captured at the battle of Weldon Railroad. Surviving three Confederate prisons, he suffered various ailments, the result of eating rats and living in damp holes in the ground. Horace Kellogg (1845-1917), originally from Patten, was 18 when he joined the war as a drummer boy. He was at the surrender of Lee at Appomattox, but before the war ended he suffered with typhoid fever. Mr. Kellogg ran the first store in Vanceboro and became a prominent member of the community. Both Mansfield and Kellogg fought bravely in the 16th Maine. As some of the first community members, the three veterans helped Vanceboro grow into a vibrant little village.

Swaney, Mansfield, and Kellogg were not the only Civil War soldiers who returned to Vanceboro after the war. In fact, a total of 12 veterans were living in town in 1890, documented by Horace Kellogg as part of the 1890 federal census (see list to left).

One can imagine these soldiers celebrating, as they watch their General, then President Grant, dedicate the European and North American railway on a sunny October 19, 1871 afternoon. Perhaps they manned the cannon that marked the celebration of “Vanceboro’s Greatest Day” and then lunched together with over a thousand others under the expansive white tent erected for the occasion.

World War I

The US entered the Great War in 1917, three years after Canada. So when German saboteur, Werner Horn, attempted to blow up the rail bridge between Vanceboro and St. Croix in the winter of 1915, he did so from the American side. His attempt to disrupt the supply train from the U.S. to Europe via harbors in St. John and Halifax failed, but because the U.S. was still neutral, Horn was arrested only for traveling with illegal explosives and for mischief since the explosion broke windows around town.

So closely entwined with their Canadian friends and relatives, people in Vanceboro followed the early years of the war, listening for news about outfits like the Royal Winnipeg Rifles, the Black Watch, the Nova Scotia Highlanders, and the Queen’s Own Regiment. They heard of the awful retreat at Mons, the Battle of Ypres, and the brave Battle of Vimy Ridge. And so, by the time the U.S. entered World War I, the people of Vanceboro had already worried over and mourned Canadian friends and relatives.

When the United States did enter the war, 20 Vanceboro men enlisted and all but two returned. Fred J. MacDonald died on his way home from the war by boat. Roland Ferry McLaughlin (1894-1919), an infantry sharpshooter, was wounded in France’s Argonne Forest on October 7, 1918. McLaughlin returned to the US, but died on February 14, 1919 in the Army hospital at Fort McHenry, Maryland. His lungs compromised by noxious gas, his death was thought to be the result of ether induced pneumonia after a series of surgeries.

World War II

Vanceboro’s memorial honoring World War II soldiers lists 82 men. Local folks say it was closer to 100, though perhaps this number included those from surrounding towns as well. Lindy Brown recalled that “out of Vanceboro, a town of about 600 or 700 at the time, 113 went in the service.” Of those who fought, three did not return: Paul C. Nason, Forrest (Foddy) O. Tracy, and Frederick S. Mills, for whom the Vanceboro Legion was named.

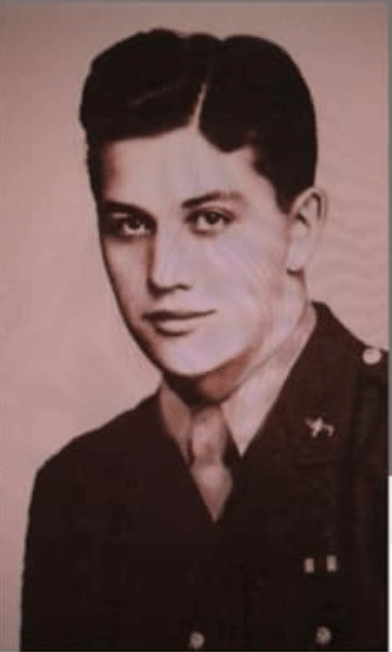

Frederick (Freddy) S. Mills was killed in action on September 27th, 1944 in Italy, where he was serving in the Medical branch of the Fifth Army. Mills received the Bronze Star for gallantry in action. The American Legion, Post #172, is named in his honor

Army private Paul Nason was killed in action on November 14, 1944, the result of a traumatic event. He was awarded the Purple Heart. Private Nason is buried in the American Cemetery in Epinal, France.

Forrest (Foddy) Tracy was reported killed in action on Anzio beachhead in Italy. His parents Arlie and Irene, received a letter from the Secretary of War dated Nov 21, 1944 informing them of their son’s death. He was just eighteen. He was awarded the Purple Heart posthumously. Margaret Kaine called Foddy “a great friend.” Lindy Brown remembers that Foddy’s mother, Irene, “had a huge picture frame with a picture of every boy from Vanceboro who went in the service.”

In an act of remarkable family courage, all five of Walter and Margaret Beer’s boys served in WWII and all five returned home safely: Cecil (Zeke) served in the Army, as did George, Raymond (Fuzzy), and Murray (Babe). Hollis (Holly) served in the Navy and later, served in the Korean War as well.

Three local nurses, Reitha Hodgkins Scribner, Josephine (Jo) Johnson Boehm, and Christianna (Chrissy) Clendenning Beers joined the war effort.

Lieutenant Jo Johnson was stationed at the U.S. Naval Receiving Hospital in San Francisco. She acted as a liaison between the Navy/Marine Corps and civilian “rest homes,” coordinating care for wounded Vets in their respective home towns.

Lieutenant Reitha Hodgkins served in the U.S. Army Nursing Corps and was among the first wave of nurses in Normandy. She was a charter member of the Frederick Mills American Legion Post in Vanceboro.

Chrissy Clendenning Beers served in the U.S. Army Nurse Corps. Stationed in France during WWII, she nursed wounded soldiers on the front lines.

Monument honoring those serving in Korea, Vietnam, Grenada, Iraq, Afghanistan, and other smaller conflicts

On Veteran’s Day, November 2021 a second honor roll was dedicated, this time listing the names of those serving in wars and conflicts following World War II. Veterans Gary Beers, Billy Grass and Harvey Day, with David Scott led the effort. As indicated on the memorial, two soldiers, Irvine Mansfield Nason and Wayne Clendenning died while serving their country.

Korean War

Master Sergeant Irvine Mansfield Nason served first in World War II in the EuropeanTheater and then, again, in Korea. He first enlisted on September 17, 1942, just over a week after he married Doris Leech from McAdam. He reenlisted in June 1947. Sergeant Nason was reported missing and later declared killed in action on December 1, 1950 during the Battle of Chosin Reservoir.

Vietnam War

U.S. Navy Machinist Mate 1.C., Wayne Clendenning, 33 years old, died on March 15, 1973 when the antisubmarine patrol plane he was aboard, a Brunswick-based P3 Orion, crashed into the Atlantic on a routine training mission. All five crew members were lost.