by Lyn Mikel Brown

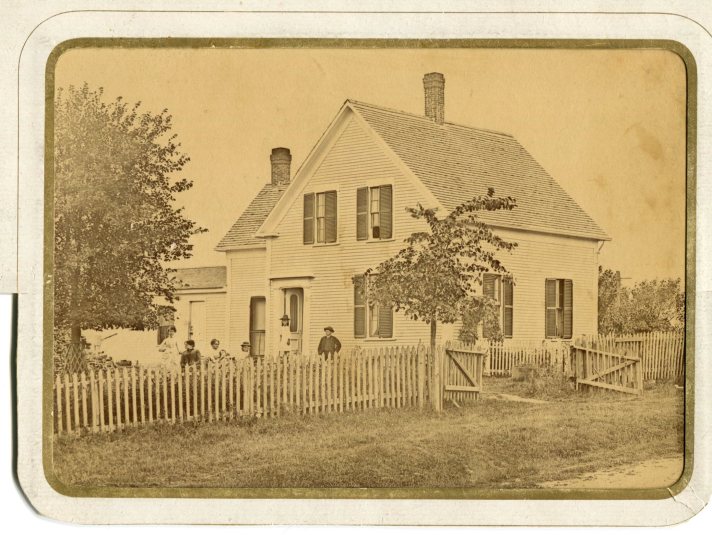

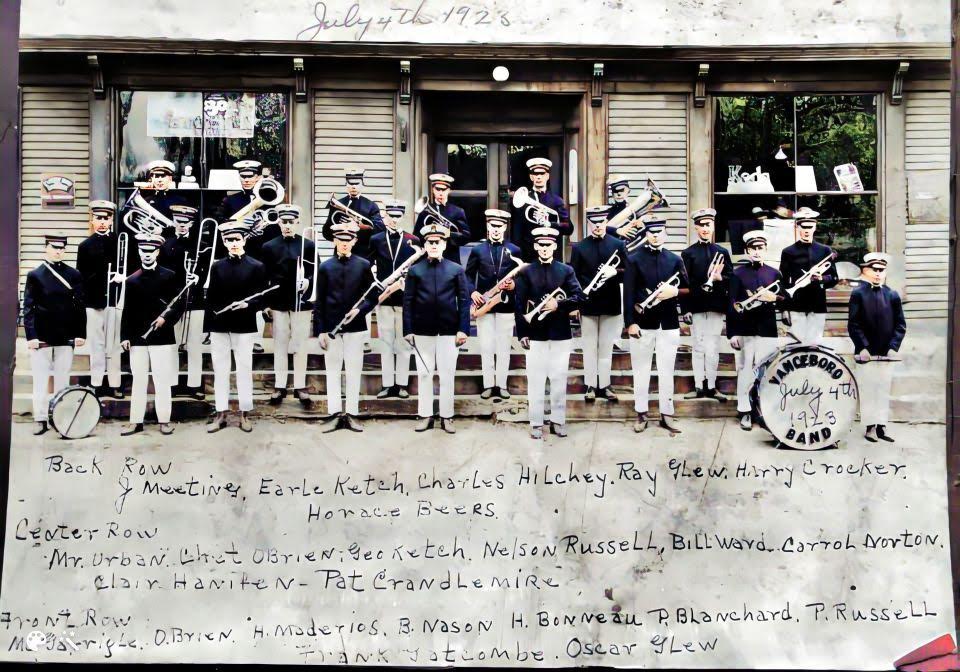

When Teresa and Richard Monk moved into their house in 1970, they discovered two big brass horns in the cellar. They’d bought the house from Lloyd Day, a customs inspector, but the instruments, they soon discovered, came from another house Mr. Day owned, once Perley Blanchard’s, a member of the Vanceboro town band. The Monks donated both horns to the Vanceboro Historial Society, where they now sit under a photo that includes Blanchard and the rest of the twenty-two uniformed band members.

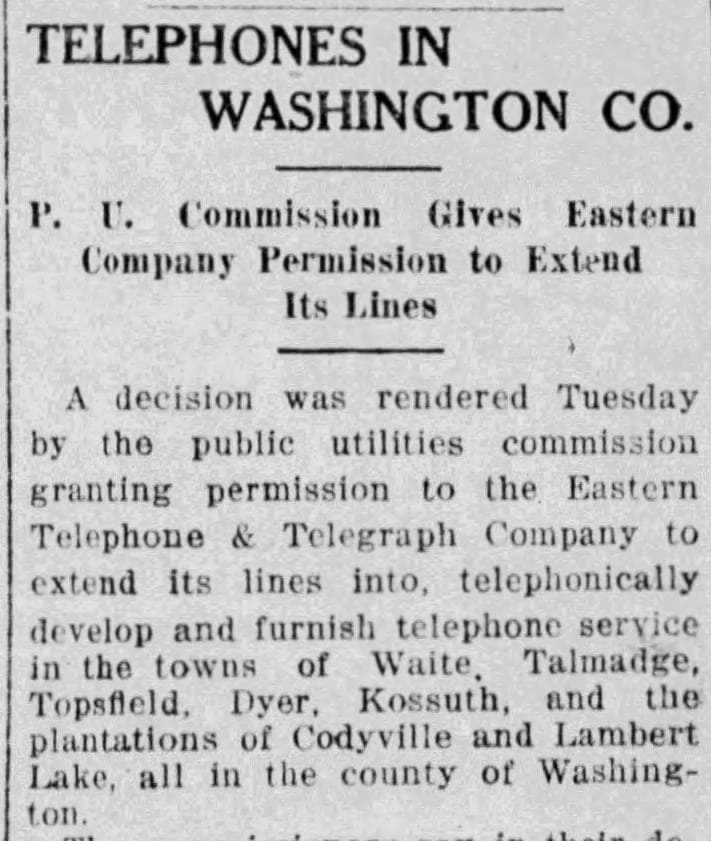

The Vanceboro Brass Band was organized and directed in 1922 by Harold Bonneau, a U.S. Customs officer who played and taught violin and clarinet. By 1925, the group was in high demand, playing for parades, at home and away ball games, offering concerts on Memorial Day and the joint celebration of Canada’s Dominion Day, July 1st, in McAdam and U.S. Independence Day, July 4th, in Vanceboro.

Every September the band traveled to the St. Stephen Exhibition, a popular county fair, complete with harness racing, stage shows, agricultural displays, and carnival rides. Bands from the surrounding area were invited, a different one on display each day of the week. The band of the day would parade from the international boundary halfway across the Ferry Point Bridge and proceed to St. Stephen, down Water Street, left onto King Street and on to the exhibition grounds.

Herb Gallison, in his memoir, The Life and Pretty Good Times of Herb Gallison writes about Vanceboro’s turn to parade on September 1925. To appreciate the story one needs to know that, prior to their departure for St. Stephen, a number of the band members had a taste of the good stuff.

On the Vanceboro Band’s day, the members assembled at the Knights of Pythias Hall, mostly bright and generally early. Uniforms pressed, white caps gleaming, duck trousers chalk white, black shoes shined, and instruments mirror-bright, except for the clarinets and drums, which were naturally dull. The members boarded various privately owned automobiles and went bumping down the old Woodstock Road with chins held high by the choker collars….Squeezing the tuba into the trunk didn’t appear to be easy. Someone was heard to remark, “That car is loaded to the gills.” It was never determined whether the remark was actually directed at the occupants.

Somewhere along the route the five-passenger sedan containing seven uniformed musicians got separated from the caravan. They finally showed up on the bridge just before the band was due to step out. Most of the musicians were not immediately aware that they had detoured through Milltown, where a certain apothecary was reputed to be dispensing the much-sought-after elixir.

The band assumed parade formation in the middle of the bridge. The command was issued and it moved out toward Canada. As it made the right-angle turn down Water Street the band was playing “The Gladiator” by Himself, John Philip Sousa. It is a difficult enough number to play while seated in a concert hall. Near the Canadian Pacific Depot the band made the sharp left turn up King Street.

In front of Burns’ Restaurant, with the thoughts of delicious boiled lobster dripping melted butter causing general salivation, the band struck up “Invercargill,” an old favorite it could play by memory in the dark. Suddenly a trolley car on the rails in the middle of the street came rattling from the direction of the band’s destination.

Something had to give, and the car coming downgrade wasn’t fixing to stop. With the old familiar march tune blaring forth, the band took a starboard tack toward Cliff Hanley’s meat market—all but the tuba player. From the front row on the extreme port quarter he swerved left and marched along the gutter in front of Johnson’s drug store, never missing a note, while the streetcar passed between him and the rest of the band. As the car creaked on by, the marchers swung back to the middle of the street and the tuba left the ditch to join formation, still Oompa-oomping those resonant bass notes.

Thanks to the Monks, the Vanceboro Historical Society has that rogue tuba. We don’t know if the tuba player had a bit to drink or if he simply made the safest maneuver. Either way, if you think it’s easy playing the Invercargill March side-stepping a trolley, give a listen.