by Lyn Mikel Brown

In the 1946 Christmas classic, It’s a Wonderful Life, George Bailey postpones his plans to see the world when his father dies suddenly and he is pressed to take over the family business. Bailey Brothers Building and Loan is committed to shoring up the community by lending money to families who couldn’t qualify for loans from banks to build homes and George finds himself battling the “richest and meanest man in town,” banker and slum lord, Henry Potter. After a series of unfortunate events, facing the loss of the Building and Loan, George nearly jumps from a bridge into the river. He’s rescued by an angel, Clarence, who shows George what his family and his town of Bedford Falls would be without his generosity and decency: the dark, soulless town of Pottersville.

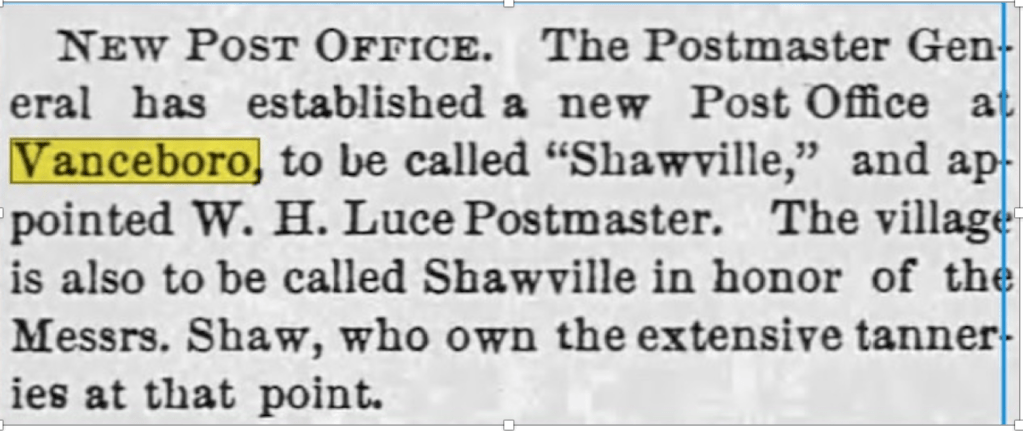

This holiday season, we give thanks to the early citizens of Vanceboro, who withstood the efforts of the Shaw brothers, owners of the tannery, to rename the town “Shawville.”

F. Shaw & Bros

F. Shaw & Bros was a Boston firm that dominated the Maine tannery business in the late 1800’s. There were Shaw tanneries in Kingman, Jackson Brook (now Brookton), Forest City and Grand Lake Stream (formerly Hinckleytown Plantation). Vanceboro was an especially attractive location because of the railroad and the promised completion of the transcontinental European & North American Railway.

The tannery arrived in 1869 to a small collection of logging camps. By 1870 Vanceboro and Lambert Lake combined had a population of 573. In 1873, the tannery consisted of 12 machines worked by 40-60 employees and produced more than 60 tons of shoe-sole leather. Each worker was paid $8 per week. The town grew to over a thousand.

Early Vanceboro was, in essence, a Shaw Bros company town: a saw mill, a stable and blacksmith shop, a public hall, a company store. In time, there was a school, a church, a hotel and rail station. The Shaws built a number of large family homes and establishments in town. Some, like Thaxter Shaw’s off First Street, had wrap around porches and grand views of the river.

Workers, though, lived in tenement houses down on the flats, closer to the tannery. The work was difficult and dirty, the chemicals toxic. The operation dumped waste directly into the water: salt liquor from soaking skins, lime liquor used to swell skins and loosen hair, waste tan liquor, tan-bark refuse after leaching. As the business boomed, waste polluted the St. Croix and damaged the spawning beds of landlocked salmon and brook trout.

On a sunny October 19th, 1871, President Ulysses S. Grant arrived in Vanceboro to great fanfare. According to the Bangor Daily Whig and Courier, thousands arrived to watch the President drive a golden spike to dedicate the transcontinental rail line that would send goods across the border to ports in St. John, New Brunswick and on to Europe.

The Shaws wasted no time. Less than two weeks after the celebration, on October 31, 1871, the Bangor Daily Whig and Courier, reported the town was “to be called Shawville in honor of the Messrs. Shaw, who own the extensive tanneries at that point.”

It wasn’t to be for long. On Nov 23, 1871, the Bangor Daily Whig and Courier reports a reversal of the decision. Shawville will be Vanceboro once again.

We don’t know what happened. Maybe the change to Shawville was made illegally, a kind of entitled name grab that caught the attention of authorities? Maybe local townspeople, like those in the fictional Bedford Falls, gathered together in support of the greater good, refusing to be used as a company town by a wealthy landowner? We like to think it was the latter.

In 1874, the town was officially incorporated as Vanceboro. In 1883, the immense Shaw operations failed. Unlike other tannery towns, Vanceboro weathered the loss, in large part because of the railroad and the opportunities it offered. People bought back Shaw properties, elected town leaders, and reimagined their future.

Merry Christmas and Happy New Year to all from the Vanceboro Historical Society and the little town that could.